By Cynthia Atuchukwu

Water & Uganda

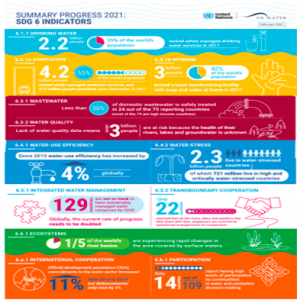

Water is Life. It is an essential natural resource, yet about 2.2 billion people lack access to safe drinking water (see Appendix I), and 785 million people living in rural areas lack access to it.[i] The Republic of Uganda is a landlocked country located in East Africa, whose capital is Kampala.[ii] Its landscape encompasses the snow-capped Rwenzori Mountains and Lake Victoria. In Uganda, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was reported on 21st March 2020.[iii] As millions of people are trying to navigate the new COVID-19 era with the added challenge of living without access to safe water, sanitation, and quality education. Now, more than ever, access to water is critical to every family’s health in Uganda, especially for those 1 in 9 people who lack access to safe water and the 1 in 3 people who lack access to a toilet.[iv] According to the 2020 World Economic Forum report, in terms of short-term risk global shapers and global risk impact on society, the water crisis is 86% and 5th compared to other indicators.[v]

Since the coronavirus outbreak, no country has been left untouched in its wake and has set an unprecedented global impact.[vi] The COVID-19 pandemic reveals that billions of people worldwide still do not have access to safe water and sanitation, especially in the least developed countries, proving that the world has not yet achieved the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (UN SDG) 6.[vii] The UN SDG 6 is crucial in society’s sustainable development.[viii]Sanitation and access to safe water are human rights; therefore, access to these services, including water and soap for handwashing, is an integral part of human well-being. It is essential to clearly state the difference between “water rights” and “human rights to water and sanitation.”

Water rights are given to an individual or organization through property rights or land rights or a negotiated agreement between the state and landowners.[ix] It is usually regulated by national laws and is temporary and can be revoked. On the contrary, the human rights to water and sanitation are neither temporary nor require state approval as these rights cannot be withdrawn.[x] Water is essential for improving nutrition, preventing diseases, and ensuring women and girls’ full participation in school activities.[xi] It is crucial in managing risks related to famine, disease epidemics, inequalities, and natural disasters.[xii]

Although the coronavirus is a health pandemic, its impact transcends health, impacting both the economy and society’s welfare. The containment of this virus has further led to a slowdown in Uganda’s economic and educational activities.[xiii] The country’s water and sanitation services have been stressed due to the high population growth resulting from its economic growth in the past two decades, leading to large population movements from rural to urban areas. About 8 million Ugandans do not have access to safe water, and nearly 27 million do not have access to sanitation facilities. Due to disparities in access to water in Uganda, many urban people living in poverty pay as much as 22 percent of their income to have access to water vendors and services. Moreover, spending a substantial part of their income on water reduces their household income, thereby limiting their chances of saving and breaking the cycle of poverty.[xiv]

The world has been witnessing the highest levels of human displacement on record. Armed conflict, persecution, and climate change, in tandem with poverty, inequality, urban population growth, poor land use management, and weak governance, are increasing the risk of displacement and its impacts.[xv] Women and children make up the majority people found in the internally displaced people (IDPs) camps. Uganda is the largest refugee-hosting African country, and it is estimated that by the end of 2021, the country’s refugee population would be 1,484,356.[xvi] Women in these centers face barriers to access essential sanitation services, water supply, and education.[xvii] Most importantly, women and children’s access to these resources is limited due to the pandemic and mass displacement, which further strained water resources and related services.[xviii] Women in these centers deserve to receive higher-quality water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities, especially during this pandemic, because it is their basic human right. It will also help stop the spread of the virus at the facilities.

Epidemic & Education

In recent years, Uganda’s educational system has changed significantly, thus, it is still lacking in many areas. Uganda has made steady progress towards achieving the UN SDGs by ensuring that more children have access to quality education, live in clean environments, and are kept safe from violence and exploitation.[xix] The Uganda government recognizes the importance of education as a basic human right and it continues to strive to provide free primary education to all children in the country (see Appendix II). However, the rapid influx of refugees, urbanization, increasing poverty, droughts, floods, and disease outbreaks continues to pressurize the governments need to improve in security, education, and health sectors across the country.[xx]

UNESCO reports estimates that by late March 2020, more than 190 countries had shut schools to slow the spread of COVID-19, disrupting nearly 1.6 billion students’ education.[xxi] A study on past school closures shows that any interruption in education, including regularly scheduled breaks, can result in a significant learning loss.[xxii] For example, in Malawi, the transitional interruption from grade 1 to grade 2 and grade 2 to grade 3 resulted in a 0.4 drop in the average standard deviation of the four different reading skills.[xxiii]

Many scholars note that measuring school closures’ impact due to extreme weather conditions, natural disasters, and disease epidemics point to severe learning consequences for students, especially those in the least developed countries.[xxiv] For instance, in Maryland, United States, for each day schools were closed due to snow, the number of students who performed satisfactorily on state reading and mathematics evaluations diminished by 0.5 percent.[xxv] After the Pakistan earthquake in 2005, the school was closed for 3.5 months, causing learning losses, equivalent to 1.5 school grades.[xxvi] The Ebola outbreak in 2013-2014 in West Africa led to the prolonged closure of schools that severely caused an impact on education, such as reduced school attendance, increased dropouts, and effects on other critical child-related outcomes such as increased risks of violence and abuse, teenage pregnancy, and child labor.[xxvii] Uganda is also experiencing the impact of long-term school closures on education. Due to the closure of schools in more than 51,000 institutions in Uganda because of Covid-19 outbreak, approximately 15 million children, including 600,000 refugee children, are out of school.[xxviii] These children especially young girls are at increased risk of violence, exploitation, and abuse.

Water & Epidemic

Since the 1980s, due to the combined effects of population growth, socio-economic development, and changing consumption patterns, the world’s water consumption has increased at a rate of approximately 1% every year.[xxix] It is estimated that by 2050, the global water demand will continue to grow at a similar rate, accounting for 20% to 30% of current water consumption, mainly due to the growth of industrial and domestic water demand.[xxx] For at least one month of the year, more than 2 billion people live in countries with severe water shortages, and about 4 billion people suffer from severe water shortages.[xxxi] As water demand increases and the impact of climate change intensifies, stress levels will continue to increase.[xxxii]

In terms of both storage and supply delivery and improved drinking water and sanitation services, the lack of water management infrastructure plays a direct role in the persistence of poverty in sub-Saharan Africa.[xxxiii] People living in rural areas account for about 60% of sub-Saharan Africa’s total population, and many remain in poverty.[xxxiv] However, providing this growing population with access to WASH services is not the only challenge for Africa, as the demands for energy, food, jobs, healthcare, and education will also increase. Population growth primarily occurs in urban areas, and without proper planning, this might lead to a dramatic increase in slums.[xxxv] These slums will be filled with women, young girls, and children who still lack safe water and sanitation, making them vulnerable to diseases.

About half of the people drinking water from unprotected sources live in Sub-Saharan Africa.[xxxvi] Six out of ten people do not have access to safely managed health services.[xxxvii] However, these global figures mask significant inequities between and within regions, countries, communities, and even neighborhoods. According to the UN Water Report (2020), the global cost-benefit outlined shows that WASH services provide good social and economic returns when compared with their costs.[xxxviii] It has a global average cost-benefit ratio of 5.5 for improved sanitation and 2.0 improved drinking water.[xxxix] The benefits of improved WASH services for vulnerable groups would change the balance of any cost-benefit analysis that accounts for changes in these groups’ self-perceived social status and dignity.[xl]

According to the 2020 UNICEF situation report in Uganda, the moderate to heavy local rainfall in April, May, and November 2020 caused widespread floods across the country, including around Lake Victoria, Lake Albert, Lake Kyoga, and southern Karamoja.[xli] The flood destroyed houses, crops, infrastructure, and disrupted livelihood activities. The disaster displaced nearly 102,671 people, and approximately 799,796 people were affected.[xlii] As a result of the floods, infectious diseases broke out in the country, including an outbreak of cholera and an increase in malaria cases.

The value and impact of water on epidemic outbreaks in the society can be seen in its use in the containment of the Ebola outbreak in Africa. In August 2018, the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, led to several associated and imported cases of the epidemic in Uganda. The epidemic further puts additional strains on Uganda’s already overstretched social services given the sporadic outbreaks of cholera and Congo-Crimean Hemorrhagic fever.[xliii] In collaboration with UNICEF, Uganda’s government provided infrastructure development, capacity building, WASH supplies, and about 5,600 portable hand-washing equipment and renewable supplies to facilities and schools, including over 26,000 kg of soap to stop the spread of Ebola in the country.[xliv] Therefore, it is crucial to address the global water crisis as safeguarding this resource is beneficial to the society and essential in containing the spread of COVID-19 in the world.[xlv]

The Gender Left Behind

In society, discrimination can happen in many ways such as indirect or direct, and it can be for varied reasons. Direct discrimination occurs when people are discriminated against by policies, laws, or practices that deliberately exclude them from providing services or equal treatment.[xlvi] On the other hand, when policies, regulations, or procedures appear to be neutral on the surface, but in reality, such discrimination has the effect of precluding the provision of essential services.[xlvii] It is termed indirect discrimination.[xlviii] Women and girls often face discrimination and unequal treatment concerning their human rights to safe drinking water, sanitation, and access to quality education in many parts of the world specially in Africa. There are many reasons for discrimination, but poverty usually accounts for a large proportion. Women and young girls in poor rural areas are not covered by water and sanitation services. In these areas, water infrastructure remains extremely sparse.[xlix]

Although the global water crisis and lack of access to quality education affect all groups in society, the impact on women and girls is much greater. It increases gender inequalities and threatens their health, well-being, livelihoods, and education. In times of drought, women and girls are likely to spend a long-time collecting water from more distant sources, putting girls’ education at risk as it reduces their attendance.[l] Women and girls are exposed disproportionately to the dangers of waterborne diseases during floods due to lack of access to safe water, the disruption of water services, and increased water resource contamination. Integrating gender in early warning systems is essential, as women and children are 14 times more likely than men to die during a disaster, experience violence and exploitation.[li] In many regions, inadequate WASH facilities’, and social and economic burden lies disproportionately on women and girls.[lii] For instance, due to water collection tasks and shame about toilet use and menstrual hygiene management; women and young girls are likely to lose job and educational opportunities. However, this gender discrimination can be bridged by providing similar facilities in schools. The provision of safe drinking water and sanitation facilities at home, schools and the workplace can reduce absenteeism, especially among adolescent girls and improve women’s productivity and health.

Conclusion:

The global pandemic has revealed that women’s and children’s rights to quality education, safe water, and sanitation must be prioritized and protected by law more than ever. This article asserts that loss in foundational learning is the most difficult to recover, hence the need to promote, develop and refine methods of learning in and outside of school, especially in the least developed countries such as Uganda. It is essential to promote multiple delivery channels for better inclusivity regardless of technological constraints. Every human being deserves to define their future, and access to water and education make that possible. Water connects all aspects of life. Providing and accessing safe water and sanitation facilities, especially for women and children, can give them time to go to school and work and improve their health. In this new COVID-19 era, access to safe water can protect and save many lives, especially those in the developing countries and at the same time, unlocking economic prosperity and improving young girls’ school attendance.

Appendix I

Source: Water.org. (2021). Summary Progress Update 2021: SDG 6 – water and sanitation for all: UN-Water. UN. https://www.unwater.org/publications/summary-progress-update-2021-sdg-6-water-and-sanitation-for-all/.

Appendix II

Source: UNICEF (2015). Situation Analysis of Children in Uganda Available at: https://www.unicef.org/uganda/what-we-do/wash.

[i] Water.org. (2021, February 24). Summary Progress Update 2021: SDG 6 – water and sanitation for all: UN-Water. UN. https://www.unwater.org/publications/summary-progress-update-2021-sdg-6-water-and-sanitation-for-all/.

[ii] Kiwanuka, M. Semakula M., Kokole, . Omari H., Ingham,. Kenneth and Lyons,. Maryinez (2021, March 10). Uganda. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Uganda

[iii] UNICEF. (2021, March 12). Uganda Humanitarian Situation Report, End of Year 2020. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/documents/uganda-humanitarian-situation-report-end-year-2020.

[iv] WHO. (2018, February 22). Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/jmp-2017/en/.

[v] World Economic Forum. (2020). The Global Risks Report 2020. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2020.

[vi] UNICEF. (2020, November 1). The socio-economic impact of COVID-19 in Uganda. UNICEF Uganda. https://www.unicef.org/uganda/reports/socio-economic-impact-covid-19-uganda.

[vii] UN Water. (2020, March 1). New data on global progress towards ensuring water and sanitation for all by 2030: UN-Water. UN. https://www.unwater.org/new-data-on-global-progress-towards-ensuring-water-and-sanitation-for-all-by-2030/.

[viii] ibid

[ix] Connor, R., Uhlenbrook, S., & Koncagül, E. (2019, June 30). World Water Development Report 2019 – Leaving No One Behind. UNESDOC Digital Library. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367303.

[x] ibid

[xi] ibid

[xii] Water.org. (2021, February 24). Summary Progress Update 2021: SDG 6 – water and sanitation for all: UN-Water. UN. https://www.unwater.org/publications/summary-progress-update-2021-sdg-6-water-and-sanitation-for-all/.

[xiii] UNICEF. (2020, November 1). The socio-economic impact of COVID-19 in Uganda. UNICEF Uganda. https://www.unicef.org/uganda/reports/socio-economic-impact-covid-19-uganda

[xiv] UNICEF Uganda. (2020, April 1). UNICEF Uganda Annual Report 2019. UNICEF Uganda. https://www.unicef.org/uganda/reports/unicef-uganda-annual-report-2019.

[xv] Connor, R., Uhlenbrook, S., & Koncagül, E. (2019, June 30). World Water Development Report 2019 – Leaving No One Behind. UNESDOC Digital Library. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367303.

[xvi] UNHCR. (n.d.). Uganda. Uganda | Global Focus. https://reporting.unhcr.org/uganda; Momodu, S. (2018, December). Uganda stands out in refugees hospitality | Africa Renewal. United Nations. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/december-2018-march-2019/uganda-stands-out-refugees-hospitality.

[xvii] Connor, R., Uhlenbrook, S., & Koncagül, E. (2019, June 30). World Water Development Report 2019 – Leaving No One Behind. UNESDOC Digital Library. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367303.

[xviii] ibid

[xix] UNICEF Uganda. (2020, April 1). UNICEF Uganda Annual Report 2019. UNICEF Uganda. https://www.unicef.org/uganda/reports/unicef-uganda-annual-report-2019.

[xx] ibid

[xxi] UNICEF. (2020, October 13). COVID-19: Effects of school closures on foundational skills and promising practices for monitoring and mitigating learning loss. UNICEF. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/1144-covid19-effects-of-school-closures-on-foundational-skills-and-promising-practices.html.

[xxii] ibid

[xxiii] ibid

[xxiv] Selbervik, H. (2020). Impacts of school closures on children in developing countries: Can we learn something from the past? CMI. https://www.cmi.no/publications/7214-impacts-of-school-closures-on-children-in-developing-countries-can-we-learn-something-from-the-past.

[xxv] Marcotte, Dave E., and Steven W. Hemelt. ‘Unscheduled school closings and student performance.’ Education Finance and Policy, vol. 3, no. 3, July 2008, pp.316–338

[xxvi] Andrabi, T., Daniels, B., & Das, J. (2020, May). Human Capital Accumulation and Disasters: Evidence from the Pakistan Earthquake of 2005. Rise programme. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISEWP_2020/039.

[xxvii] Bakrania, S., Chávez, C., Ipince, A., Rocca, M., Oliver, S., Stansfield, C., & Subrahmanian, R. (2020, May). Impacts of Pandemics and Epidemics on Child Protection: Lessons learned from a rapid review in the context of COVID-19. UNICEF. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/1104-working-paper-impacts-of-pandemics-and-epidemics-on-child-protection-lessons-learned.html; Evans, D. K., & Popova, A. (2015, February 1). Orphans and Ebola: Estimating the Secondary Impact of a Public Health Crisis. Open Knowledge Repository. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21590; BBC News Africa. (2014, November 17). In pictures: Ebola orphans. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-30019892.

[xxviii] UNICEF. (2021, March 12). Uganda Humanitarian Situation Report, End of Year 2020. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/documents/uganda-humanitarian-situation-report-end-year-2020

[xxix] UN-Water. (2020, September 15). UN World Water Development Report 2019: ‘Leaving no one behind’: UN-Water. UN. https://www.unwater.org/world-water-development-report-2019-leaving-no-one-behind/.

[xxx] ibid

[xxxi] ibid

[xxxii] Connor, R., Uhlenbrook, S., & Koncagül, E. (2019, June 30). World Water Development Report 2019 – Leaving No One Behind. UNESDOC Digital Library. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367303.

[xxxiii] ibid

[xxxiv] ibid

[xxxv] UN-Water. (2020, September 15). UN World Water Development Report 2019: ‘Leaving no one behind’: UN-Water. UN. https://www.unwater.org/world-water-development-report-2019-leaving-no-one-behind/.

[xxxvi] UN-Water. (2020, September 15). UN World Water Development Report 2019: ‘Leaving no one behind’: UN-Water. UN. https://www.unwater.org/world-water-development-report-2019-leaving-no-one-behind/.

[xxxvii] ibid

[xxxviii] ibid

[xxxix] ibid

[xl] ibid

[xli] UNICEF. (2021, March 12). Uganda Humanitarian Situation Report, End of Year 2020. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/documents/uganda-humanitarian-situation-report-end-year-2020.

[xlii] ibid

[xliii] UNICEF Uganda. (2020, April 1). UNICEF Uganda Annual Report 2019. UNICEF Uganda. https://www.unicef.org/uganda/reports/unicef-uganda-annual-report-2019.

[xliv] ibid

[xlv] UNICEF. (2020, November 1). The socio-economic impact of COVID-19 in Uganda. UNICEF Uganda. https://www.unicef.org/uganda/reports/socio-economic-impact-covid-19-uganda.

[xlvi] Connor, R., Uhlenbrook, S., & Koncagül, E. (2019, June 30). World Water Development Report 2019 – Leaving No One Behind. UNESDOC Digital Library. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367303.

[xlvii] ibid

[xlviii] ibid

[xlix] UN-Water. (2020, September 15). UN World Water Development Report 2019: ‘Leaving no one behind’: UN-Water. UN. https://www.unwater.org/world-water-development-report-2019-leaving-no-one-behind/.

[l] UNESCO WWAP. (2021, March 12). World Water Development Report 2020 – Water and Climate Change. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/themes/water-security/wwap/wwdr/2020.

[li] ibid

[lii] ibid